Research Overview

Our research program aims to understand the biophysical pathways that allow cells to edit and repair their genomes with extraordinary fidelity. The group approaches this challenge by developing and applying new experimental modalities that merge micro-/nano-engineering, single-molecule and single-cell imaging, and bioinformatics. Below, I describe ongoing research projects and future research objectives.

CRISPR-Cas Adaptive Immunity

Precision gene editing is one of the most exciting breakthroughs in modern biomedicine. This revolution has been fueled by the discovery of RNA-based CRISPR adaptive immunity in bacteria and archaea. CRISPR immunity is comprised of two pathways: degradation of foreign DNA/RNA (interference) and integration of foreign DNA fragments into the CRISPR locus (acquisition) (Fig. 1). My lab is advancing the molecular understanding of CRISPR adaptive immunity and using biophysical principles to engineer improved CRISPR enzymes.

Figure 1. Overview of CRISPR-cas adaptive immunity.

CRISPR Adaptive Immunity

CRISPR-Cas systems can both degrade pathogenic DNA and also integrate short segments of the pathogen into the host’s CRISPR locus. Together, these pathways provide immunity from infection by related pathogens. The mechanisms of how these two pathways are coordinated have remained elusive. By directly imaging all the key molecular sub-complexes, our work provides a comprehensive picture of the coordinated steps in CRISPR-based adaptive immunity. Ongoing efforts are focused on understanding: (1) how foreign DNA is selected and integrated into the CRISPR locus; (2) how accessory factors and host proteins catalyze integration of foreign DNA into the CRISPR locus; and (3) how pathogen-encoded anti-CRISPR proteins disable or co-opt CRISPR-Cas systems.

Engineering CRISPR Nucleases

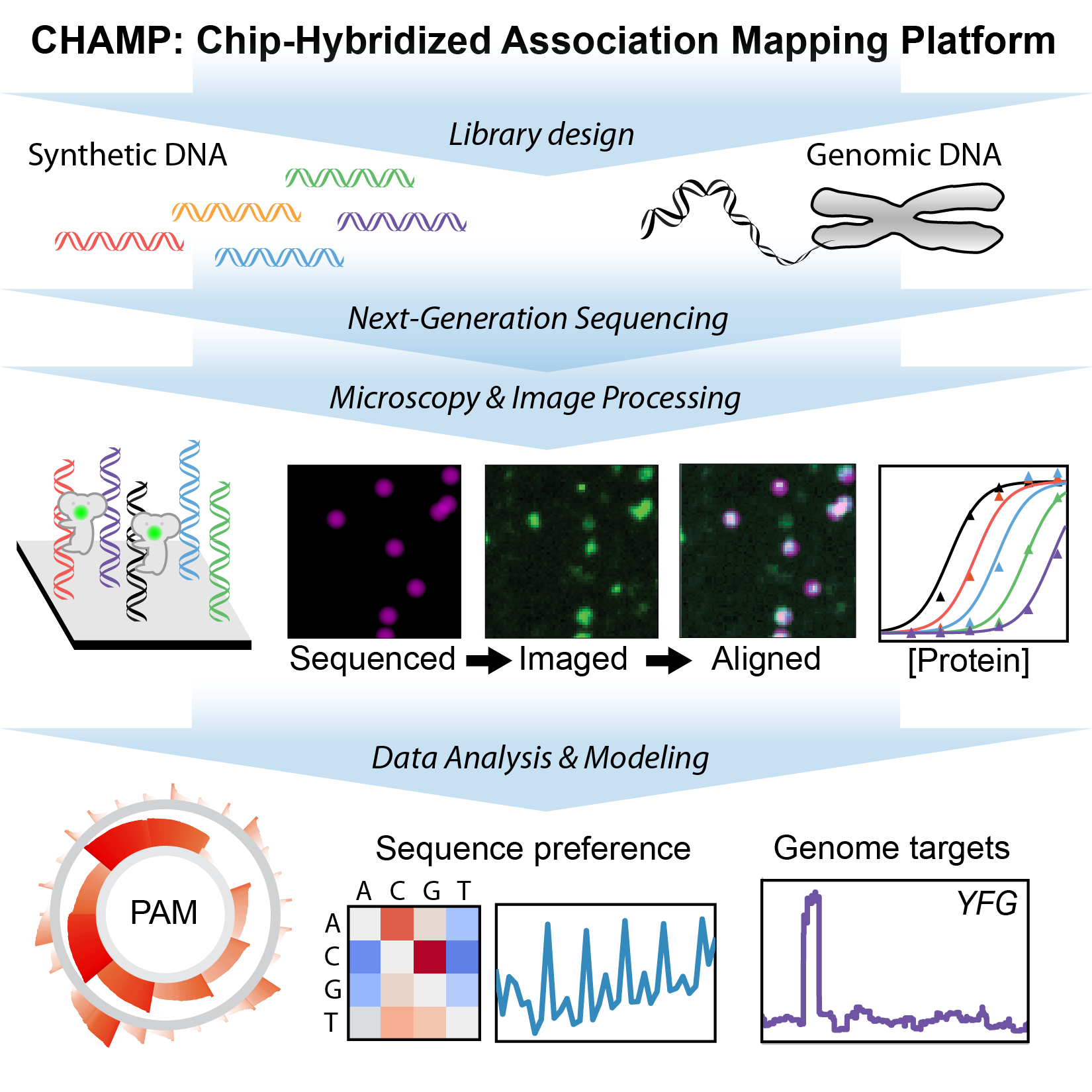

CRISPR nucleases can be rapidly programmed to cleave any genomic site via changes to their guide RNA, making them efficient tools for precision genome engineering. However, off-target DNA binding and cleavage is a pervasive program that can lead to unexpected genome modifications. We are developing new biophysical tools for profiling and improving Cas9 and related RNA-guided nucleases for improved biochemical activity and broader specificity (Fig. 2). For example, we recently repurposed commercial next-generation DNA sequencing (NGS) for massively-parallel profiling of protein-nucleic acid interactions. A key advantage of our method is that we first use commercial NGS instruments for genome-scale DNA sequencing. We then use the same microfluidic chips for structure-function studies on massive sets of sequenced genomic DNA. Using this platform, we are comprehensively characterizing engineered and wild-type Cas9s as well as emerging CRISPR nucleases such as Cas12a/Cpf1. By merging our genome-scale in vitro results with in silico DNA binding predictions and in vivo methods, we are defining how the intrinsic properties of these enzymes shape target recognition.

Figure 2. Chip-hybridized affinity mapping platform (CHAMP) repurposes old NGS chips for high-throughput biophysics.

Eukaryotic Genome Maintenance

Our genomes are constantly accruing damage that can lead to cancer-promoting mutations. DNA repair proteins serve as the molecular caretakers of the genome. An emerging theme from both cell biology and biochemical studies is that eukaryotic DNA repair pathways require the molecular choreography of multiple repair proteins at the damage site. We are using single-molecule fluorescence imaging to decipher how repair enzymes collaborate to repair our genomes.

Repair of DNA Breaks Via Homologous Recombination

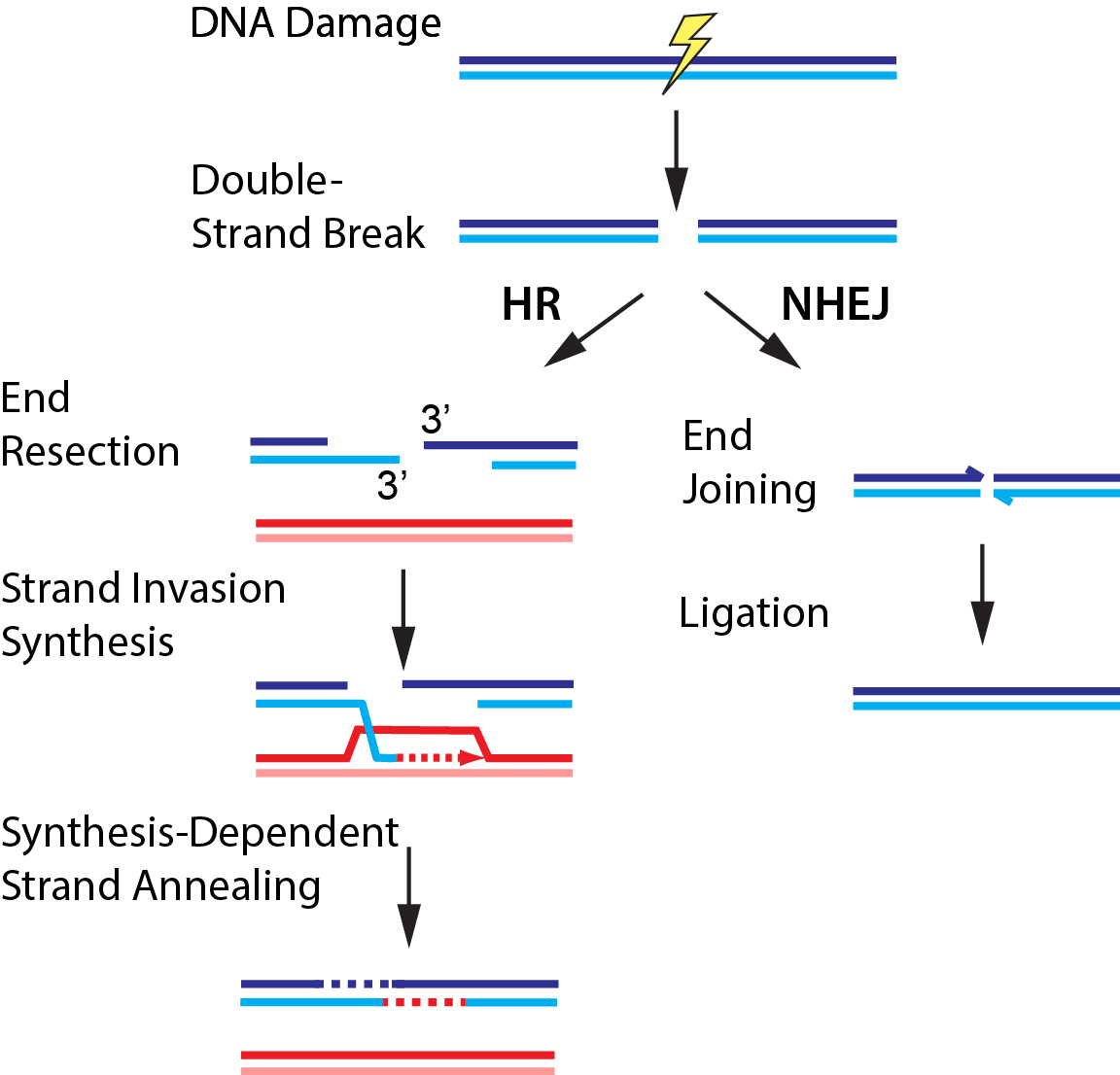

Double-strand breaks (DSBs) occur when both strands of the DNA duplex are cleaved in close proximity, fragmenting the chromosome into two distinct pieces (Fig. 3). Each of our cells must repair upwards of ~50 DSBs that arise spontaneously per cell cycle. DSBs also occur as a result of radio- and chemotherapeutics, which remain our frontline treatments for cancer. The global importance of DSB repair is illustrated by the severe cancer syndromes in patients with disruptions in any of these proteins. Using quantitative single-molecule imaging, we are tackling these longest-standing questions in the DNA break repair field: (1) How do DNA repair enzymes locate DSBs? (2) How does the coordinated assembly of these enzymes define a specific repair pathway? and (3) How does DNA repair proceed on chromatin? For example, we also reconstituted and biophysically characterized the “resectosome,” a multi-enzyme molecular machine that catalyzes the nucleolytic processing of free DNA ends to promote homologous recombination. Ongoing efforts aim to understand how chromatin and additional accessory factors regulate these key steps in HR.

Figure 3. DNA break repair via homologous recombination (HR) or non-homologous end joining (NHEJ).

Post-Replicative DNA Mismatch Repair

The eukaryotic replication machinery incorporates an incorrect nucleotide roughly once per million duplicated base pairs. These rare errors must be identified and repaired quickly, as the next round of replication cannot discriminate correct parental DNA from the incorrect daughter strand. We have recently used high-throughput single-molecule imaging to directly observe how the eukaryotic post-replicative mismatch repair machinery identifies these rare errors amidst a vast pool of error-free DNA. We are also exploring how the mismatch repair machinery is assembled at the lesion, how downstream mismatch repair is coupled to the initial lesion recognition, and how the entire pathway operates on chromatin.

DNA repair and premature aging

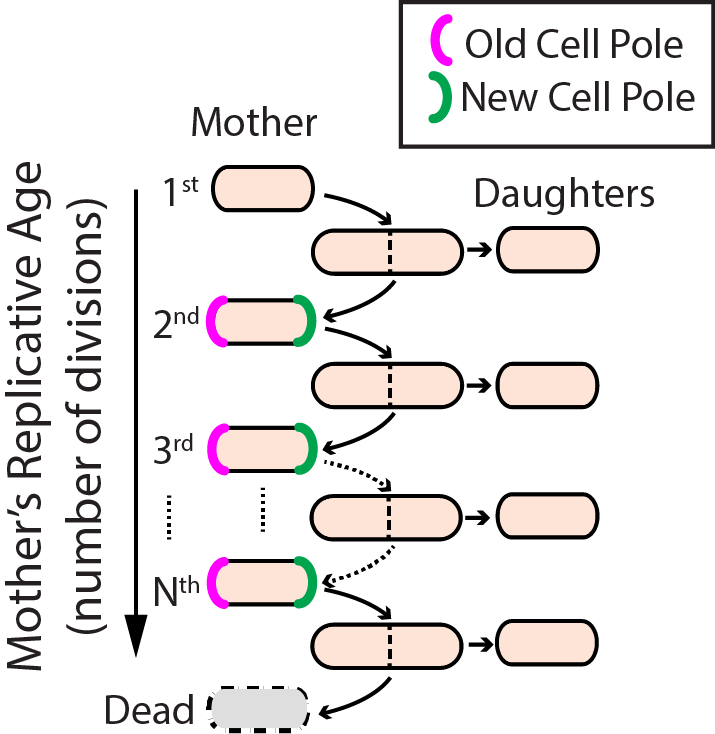

Aging–the progressive decline of function–is the leading risk factor for nearly every human disease. Defects in DNA repair pathways can accelerate aging at both the organismal and cellular levels. However, we still do not understand how cells avoid damage accumulation, renew cell vitality, or how dysregulation in these pathways leads to cell death. We use replicative aging in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe (S. pombe) as a model system for understanding how DNA damage leads to premature aging in mitotically dividing cells (Fig. 4). Specifically, we are investigating the links between genome maintenance, epigenetic inheritance, and premature aging. A growing body of both cell biological and functional genomics studies conclude that S. pombe and human cells share similar biological pathways of DNA repair, cell cycle regulation, and mitochondrial maintenance. S. pombe is also amenable to both genetic and physical manipulation, and divides rapidly enough to tractably monitor all replication events for a given cell. For these reasons, we have developed a high-throughput microfluidic strategy for capturing and observing individual S. pombe cells over their entire lifespan (see below).

Figure 4. Replicative lifespan in fission yeast.

Our lab uses Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence Microscopy (TIRFM) as the primary tool for single-molecule fluorescence imaging (Fig. 5). For TIRFM, laser excitation is limited to a shallow (~100 nanometer) penetration depth near the surface of a microfluidic flowcell. Molecules of interest are immobilized on a passivated flowcell surface, thus eliminating spurious background signals. Images are collected with a microscope objective and recorded using a back-illuminated charge-coupled device (CCD) with on-chip signal amplification. The CCD can be used with an image-splitter containing a dichroic mirror to separate the multicolor fluorescence signal for simultaneous multi-color imaging.

Figure 5. Total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy.

DNA Curtains

Collecting statistically relevant datasets is a major intrinsic challenge for experiments designed to observe individual reactions. We develop a high-throughput approach called “DNA curtains” to construct aligned arrays of surface-tethered DNA molecules (Fig. 6). DNA curtains allow us to observe hundreds of biochemical reactions simultaneously at the single molecule level with excellent signal to noise and a wide choice of excitation and emission options. Furthermore, by nanofabricating various DNA curtain geometries, we can control critical experimental parameters such as DNA orientation, spacing, density and tension.

Figure 6. DNA Curtains: a high-throughput platform for single-molecule nucleic acid biochemistry.

Microfluidic single-cell capture

Replicative lifespan studies require the microdissection of progeny cells, often for dozens of generations. These studies are laborious, low-throughput, and have largely remained unchanged since their introduction in 1959. Manual microdissection is especially challenging when the sibling cells are phenotypically similar, as occurs during fission yeast division. To address these challenges, we have developed the Fission Yeast Lifespan Microdissector (FYLM), a high-throughput microfluidic cell capture and microdissection device (Fig. 7). With the FYLM, we can concurrently image the entire lifespan of thousands of individually addressable cells for over a week, while still maintaining sub-minute temporal resolution. Each cell is continuously supplied with fresh media, and imaged with subcellular resolution using brightfield and fluorescent microscopy.

Figure 7. Multi-day single cell capture and imaging in the fission yeast lifespan microdissector (FYLM).

We have also developed a semi-automated image analysis pipeline that permits quantitative analysis of each cell’s shape, doubling time, and fluorescent reporters. Like flow cytometry, this methodology yields single-cell level analysis in addition to population analysis, and cells can be extracted from the device for downstream manipulation. By combining our high-throughput FYLM technology with comprehensive lifespan analysis, this platform offers a unique approach to study long-lived mitotically active cells.